Taken from Austin Woodbury's Ethics notes (John N. Deely and Antony F. Russell Collection, St. Vincent College, Latrobe, PA)

A few quick words on moral objects

Alas, I have been quite busy—and how I wished to be involved in posting content here. I have been toiling away at teaching, editing two Garrigou-Lagrange translations while also working on another translation-cum-commentary volume (unnamed for now, until I am sure I have a publisher).

This latter volume started as a project just to straighten up my own thoughts on some basics. However, it has become a good locale for proposing the old Thomist's school's distinction between moral and physical being. Alas, Martin Rhonheimer (whom many disagree with, often for rather cryptic reasons, I think) has seen some of this with great depth; however, he has made an unfortunate remark in Martin Rhonheimer, “The Perspective of the Acting Person and the Nature of Practical Reason: The ‘Object of the Human Act’ in Thomistic Anthropology of Action,” in The Perspective of the Acting Person: Essays in the Renewal of Thomsitic Moral Philosophy (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2008), 212-213:

Every deliberately chosen human act, on the other hand, already necessarily has an object at the moral level, because its object is this exterior act itself, as a “good understood and ordered by reason.” To deny this is to fall into physicalism. Traditionally, to avoid this danger, it was customary at this point to resort to the Deus ex machina of the mysterious “transcendental relation of the physical object to the moral norm.” This solution, however, more juridical than moral, hindered a proper understanding of the intrinsic constitution of the moral object, and therefore also of the goodness or evil that human acts intrinsically possess on the basis of their object. To avoid the necessity of recourse to this Deus ex machina or—light those who were aware of the inadequacy of this “legalistic” solution and rebelled against it—to avoid ending up in proportionalism or consequentialism (which are nothing other than variations of the same ethical-normative extrinsicism), one must place himself “in the perspective of the acting person,” conceiving the object of a human act as the proximate end of the will, that is, as an “object rationally chosen by the deliberate will” on which “primarily and fundamentally depends the morality of the human act (Veritatis splendor, n.78).

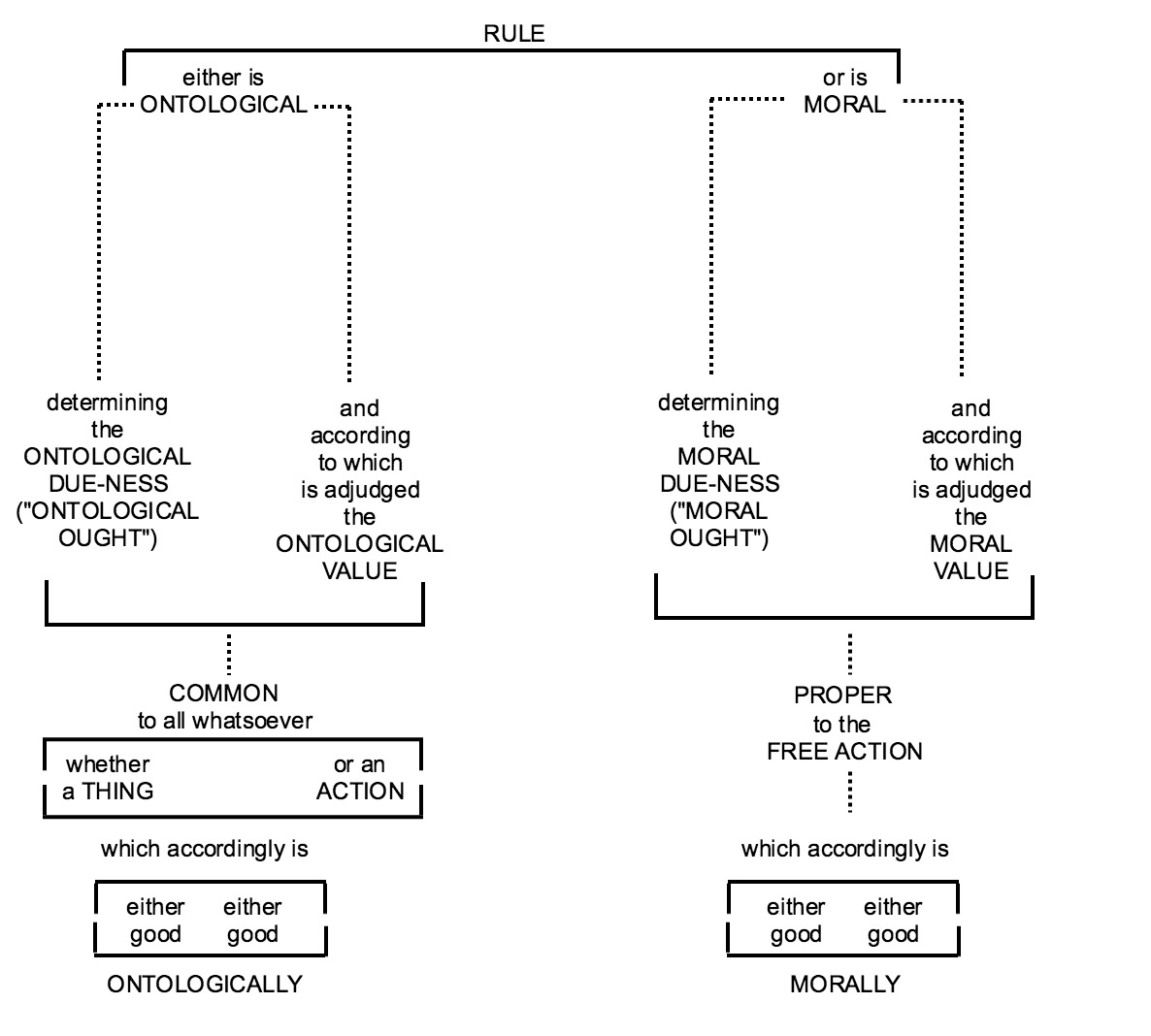

Indeed, here, one wonders about the source for this wording, whose appeal to transcendental relation clearly harkens from the Thomist school. It is neither that of Lehu nor that of the great manualists Benedict Merkelbach and Dominic Prümmer. Indeed, as can be seen in Austin Woodbury’s notes on ethics, Fr. Rhonheimer’s supposed Deus ex machina seems to be a kind of mingling of the Thomist position with the Suarezian and Nominalist conception of morality as being a merely extrinsic denomination.

See Leonard Lehu, Philosophia Moralis et Socialis (Paris: LeCoffre, 1914), n.77: “Moralitas consistit formaliter in relatione reali transcendentali actus ad regulam morum.” By “actus”, Fr. Lehu certainly does not mean “physical object.”

And also Benedictus Henricus Merkelbach, Summa theologiae moralis ad metem D. Tomae et ad normam iuris novi, 5th ed., vol. 1 (De principiis) (Paris: Desclée de Brouwer et Soc., 1947), n.115 (p.108): “Moralitas est conditio omnis actus humani et definer solet: conformitas vel disconformitas actus humani cum sua regula, recta ratione.” And, ibid., n.116 (p.109): “Sed moralitas est intrinsecus respectus seu relatio transcendentalis, i.e. intrinseca habitude ipsius actus, qua tendit ad obiectum praecise ut conforme vel difforme cum regulis morum. Est sentential Thomistarum.”

And also Dominicus M. Prümmer, Manuale theologiae moralis, 13th edition (Barcelona: Herder, 1958), cap.3 a.1 (p.68): “Moralitas actionum humanorum definiri potest: transcendentalis relatio actus humani ad normam moralitatis” and (p.71): “Moralitas consistit formaliter in tendentia (seu relatione transcendentali) ad obiectum, quatenus istud praecise substat regulis morum. Regulae autem morum sunt lex aeterna et omnia, quae derivantur a lege aeterna, ut sunt omnes alia leges iustae et conscientia. Ita explicant essentiam moralitatis omnes fere Thomiste, e.gr. Ioannes a S. Thoma, Gonet, Salmanticenses, Billuart. Ratio autem huius sententiae est, quia actus formaliter constituitur per tendentiam ad suum obiectum; tota enim ratio actus est eius obiectum. Quod quidem in ordine physico ab omnibus admittitur et per se patet; sic e.gr. actus visionis formaliter constituitur per tendentiam ad obiectum visum. Ergo a pari actus moralis essentialiter constituitur per suam tendentiam in obiectum morale. Obiectum autem est morale, in quantum subicitur regulis seu norma morum... Norma supreme obiectiva moralitatis est lex aeterna seu ratio divinae sapientiae, prout est directive omnium actionum humanarum… Norma proxima obiectiva moralitatis est ratio humana, i.e. dictamen rationis rectae, non quidem per se, sed in quantum est participatio legis aeternae.”

I plan to have more on this forthcoming, but the project is still being toiled through... I spent a good part of the day today transcribing and commenting on Woodbury's treatment of this topic.

Saving a bit on the sacraments

Emmanuel Doronzo, O.M.I., Tractatus dogmaticus de sacramentis in genere (Milwaukee: Bruce, 1946), 38.

This is more of a gem than some may realize... But I assure you, it is; a testimony to better days with brighter lights.

"Sacramentum, cum sit artefactum quoddam, seu complexus plurium rerum convenientium in unam rationem signi gratiae, dupliciter considerari potest.

Primo, in esse physico et materialiter, quatenus in eo inveniuntur plura entia ad diversa genera pertinentia, i.e. res, verba, ratio causae et ratio signi ([this may be off; not sure of what he means by this; ratio signi pertains only to relatio:]quae pertinent ad diversa praedicamenta substantiae, actionis et relationis), et sic est ens per accidens et unum per accidens, seu non unum sed plura entia, nec habet unam sed plures essentias, nec proinde una definitione definir potest aut ad unum genus reduci, sed tot habet definitiones et in tot generibus collocatur quot sunt res quibus componitur.

Secundo considerari potest, ac praecipue debet, [he slurs matters here a bit] in esse moris seu artefacti et formaliter ut sacramentum, i.e. secundum eam rationem et ordinem secundum quem omnes praedictae res in unum conveniunt, non enim mere inter se compulantur aut juxtaponuntur, quemadmodum multitudo et acervus, sed ordinantur ad unam et conveniunt in unam rationem (puta ordinantur ad unam significationem exprimendam et conveniunt in unam rationem signi gratiae); et sic sacramentum est ens per se et unum per se (quippe quod specificatur ab una per se ratione significationis gratiae) et habet unam essentiam, unam definitionem et unum determinatum genus."

A Brief Thought-Time With Searle

John R. Searle. Mind, Language and Society: Philosophy in the Real World. New York: Basic Books, 1998. (Specifically, "The Structure of the Social Universe")

Always good to get outside of your element. I am working on an unannounced translation of excellent scholastic matters. Very exciting stuff too. However, I wish to muse on the "reality of social reality." Searle has done his own little part on this, and I always admire him for eschewing the arcana of analytic philosophy's pedantic groping at pseudo-"scientific" status (in that anemic, contemporary form of science that would make Aristotle blush with shame).

Anyway, a few quotes an reactions:

"But all the same, it seems to me that there is an irreducible class of intentionality [his sense of the word, primarily practical, not too distinguished into moral / technical] that is collective intentionality or 'we-intentionality'. How can that be? In our philosophical tradition, it has always been tempting to think of collective intentionality as reducible to individual intentionality." (p.118)

Yes "our tradition"—which is not mine—is like this. He has reached a conclusion that was well articulated by Yves Simon once upon a time. (Others could be cited—Aristotle, De Koninck, McIntyre, Maritain on better days, et al.) However, Simon caps them all, and does so with class. Still, how wonderful to see Searle acknowledge it. He continues with some good examples.

See page 125 for a good example of social facts being constituted; stresses the need to shift from mere physical function (e.g. the wall protects us) to its social function solely (e.g. the wall is a border). Not sure if this can account for the distinction between human societies and those of higher animals. However, there is an intentionality in the internal senses as well. In any case, Searle does know how to make distinctions—something important indeed.

A number of good remarks after this about the way that we constitute and "stack" social realities within contexts. Doesn't ground it all well, but that's okay. One does, of course, need to articulate a complete anthropology at some point to avoid letting this lift off the ground. His remarks on teleology are not great—but we should note that, in a sense, teleology increases with complexity. Hence, one rejoices to think of phytosemiosis for instance—the "communication of flowers" with each other.

A society exists only so long as it can retain the moral being proper to it. He doesn't say it quite like this, but he sees the point: "But with the withdrawal of collective acceptance, such institutions collapse suddenly, as witness the amazing collapse of the Soviet empire in a matter of months..." (p.132) Also, some remarks on the same page (and following) about power that could be translated into "authority"; glosses quickly, but important point about how authority becomes constituted when common intentionality is constituted.

Think of some of the general issues raised here in context of physiosemiosis, phytosemiosis, biosemiosis.

I always appreciate Searle's direct style—and always walk away from him a better thinker, even if I don't agree with this or that point.